This is a companion article to our display at the Old Train Depot for the Martinez Historic Home Tour. We have 5 model trains on display, each is described below along with their relationship to the history of Martinez.

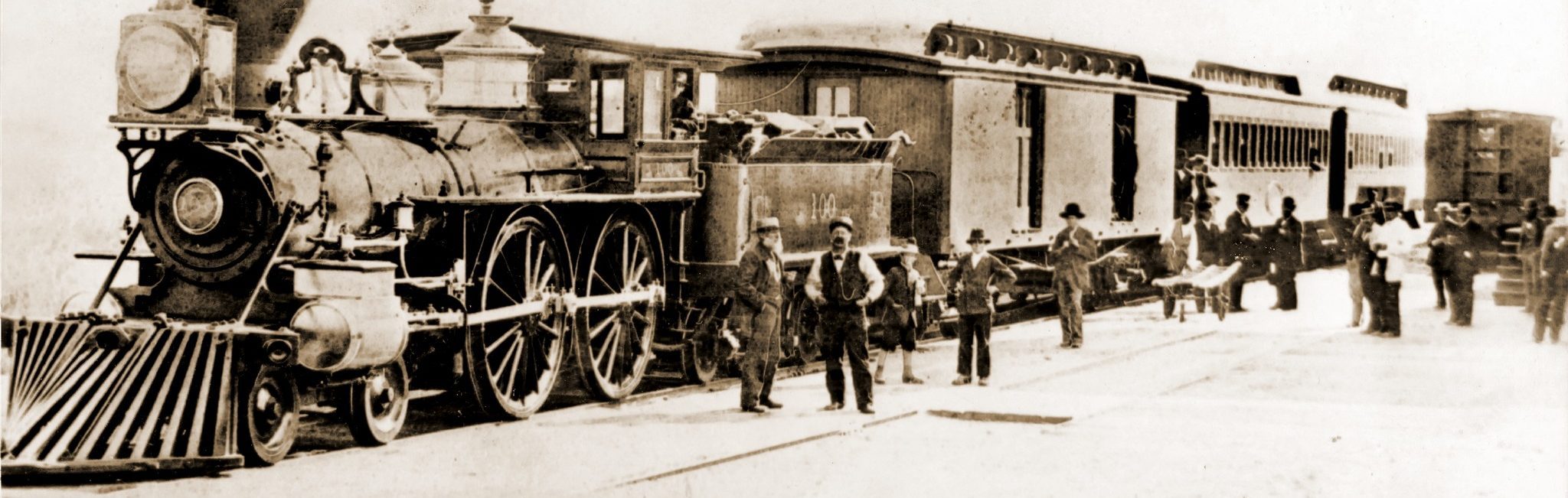

1880s Central Pacific

In the mid 1870s, through a subsidiary, the Central Pacific extended its rails from Richmond to Port Costa and Martinez. A companion project brought the rails from Tracy to Martinez. In 1878 the Martinez Train Depot was completed, one among five identical stations from Pinole to Tracy. At Port Costa a large steam ferry began operations carrying entire trains across the water to Benicia; this became the main connection for the Transcontinental Railroad into the Bay Area, replacing the original egress via the Altamont Pass and Livermore.

In the mid 1870s, through a subsidiary, the Central Pacific extended its rails from Richmond to Port Costa and Martinez. A companion project brought the rails from Tracy to Martinez. In 1878 the Martinez Train Depot was completed, one among five identical stations from Pinole to Tracy. At Port Costa a large steam ferry began operations carrying entire trains across the water to Benicia; this became the main connection for the Transcontinental Railroad into the Bay Area, replacing the original egress via the Altamont Pass and Livermore.

Shortly thereafter, in 1885, Southern Pacific took over the operation of the Central Pacific, including their locomotives, rolling stock, and stations. This was three decades after the opening of the first operational railroad in California. The two companies had different infrastructures, but for the most part common ownership, which had a virtual monopoly on West Coast railroads. These men, Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker had come together during the Civil War to finance the western leg of the Transcontinental Railroad. This investment brought them great wealth and tremendous political clout.

In the Civil War Era about 160 4-4-0 “American” locomotives were shipped to California around Cape Horn. Through mergers, most of these were owned by the Central Pacific Railroad by 1878 when their rails came to Martinez. These were versatile and abundant, though obsolete by the 1880s. The weight was well distributed across the axles, and with tall driving wheels these were able to develop high speeds for the time. The designation “4-4-0” meant that these had 4 guiding wheels in the front, 4 powered driving wheels in the middle and 0 following wheels. Guiding wheels helped to stabilize locomotives allowing higher speed.

The Train from San Ramon

In 1891 the Southern Pacific opened a branch line from just east of Martinez, at Avon, through Concord and south to San Ramon. Identical depots were built at Concord, Walnut Creek, Danville, and San Ramon. Though visually similar to the Martinez Depot, these were a newer modified design. In both cases these were considered “combination depots” meaning that these had a freight station, passenger depot, and an apartment above the depot for the station master and his family. Martinez used standard design No. 1, while the 1891 depots used standard design No. 18.

In 1891 the Southern Pacific opened a branch line from just east of Martinez, at Avon, through Concord and south to San Ramon. Identical depots were built at Concord, Walnut Creek, Danville, and San Ramon. Though visually similar to the Martinez Depot, these were a newer modified design. In both cases these were considered “combination depots” meaning that these had a freight station, passenger depot, and an apartment above the depot for the station master and his family. Martinez used standard design No. 1, while the 1891 depots used standard design No. 18.

The railroad was reluctant to add this line, but at the same time wanted to prevent competition from emerging. They drove hard bargains with the communities forcing them to contribute the easements for the rails and land for the facilities. Despite resentment, the locals banded together to raise funding, since they saw rail service as a huge boost to their economies.

At Avon there was a curved connection into the main line, only leading west toward Martinez. There was no initial plan of direct trains from this branch toward the east. Later in 1909, a curved connection was added leading east toward Pittsburg, and the rails were extended south to the other main line at Livermore/Pleasanton. Potentially this allowed a third route from the Central Valley to Oakland and San Jose, but significant usage never materialized. Even the very direct route of Tracy to Livermore was less popular because trains had to be pulled over the steep Altamont Pass. It was cheaper to send Bay Area rail traffic through Port Costa by ferry, or through the Delta, Antioch, Pittsburg, to Martinez.

By the early 1900s two types of locomotives were dominant on this line, the 2-8-0 (above) and the smaller 2-6-0. The 2-8-0 was the most numerous steam engine for the Southern Pacific in the early 1900s, while the 2-6-0 was more common on the San Ramon Branch Line. Despite seeming rather flat, San Ramon is almost 500 feet higher than Martinez, and smaller engines struggled with larger heavier trains. With fewer leading wheels, two wheels on one axle, these had a bit less high speed stability than the older 4-4-0 engines, but with six or eight driving wheels they had tremendous tractive effort allowing longer and heavier trains, and superior performance pulling uphill.

This line remained active into the early 1970s, but by the 1930s passenger traffic was minimal, while agricultural products dominated the rail traffic. The availability of cars and buses reduced the demand for slower railroad travel, and competing electric trains had emerged. Even the Southern Pacific had switched to electric passenger trains in the final years. Through WWI and WWII much of the freight on the line was agricultural, at first wheat and grain, but the railroad allowed fruits and nuts to become more practical in the valley.

Prior to the demise of passenger traffic, a typical train from San Ramon would include mixed cars of passenger and freight. The trains also hauled the mail in Express Cars, which were similar in construction and look to passenger cars, but with large doors and fewer windows. By the early 1900s Pullman Company was the major producer of these and passenger cars. Most of these on the Southern Pacific were painted Pullman Green. By the 1900s long distance passenger cars were in the 80′ range, but most cars seen on the San Ramon Branch lines were in the 60′ range — lighter and more versatile. Since it was a short trip from San Ramon to Oakland, the cars were simpler, without sleepers and dining cars. The most common would have been a “Chair Coach” with rows of simple chair-seating and few frills.

Prior to the demise of passenger traffic, a typical train from San Ramon would include mixed cars of passenger and freight. The trains also hauled the mail in Express Cars, which were similar in construction and look to passenger cars, but with large doors and fewer windows. By the early 1900s Pullman Company was the major producer of these and passenger cars. Most of these on the Southern Pacific were painted Pullman Green. By the 1900s long distance passenger cars were in the 80′ range, but most cars seen on the San Ramon Branch lines were in the 60′ range — lighter and more versatile. Since it was a short trip from San Ramon to Oakland, the cars were simpler, without sleepers and dining cars. The most common would have been a “Chair Coach” with rows of simple chair-seating and few frills.

Another common car was the orange or yellow refrigerated cars of the Pacific Fruit Express, the largest refrigerator car provider in the world, based in San Francisco. These cars were specially built to carry fruit and produce cooled by ice in the beginning and later with mechanical refrigeration. The early cars had ice compartments at each end which were loaded through hatches in the roof. These could be topped off along the route at icing stations, making long distance delivery of our local produce practical.

In the post WWII era agriculture declined in the valley, and the dominant flow of freight reversed bringing construction materials to fuel the building boom from Concord to San Ramon. But by the 1970s rail traffic in the area was obsolete. Much of the right of way is now bike lanes.

The Owl Limited

Beginning in 1878, the primary route in and out of the Bay Area was from Port Costa to Benicia, over the water by ferry. But with trackage through the Delta, from Martinez to Tracy, less critical trains or traffic to the south used this route. Though there were tracks directly from San Francisco/Oakland to San Jose then south to Los Angeles it was often more economical to send the trains to Los Angeles, via Martinez and the Delta. Much of the rail traffic out of San Francisco was carried across the water by ferry to either Oakland or Richmond. Passengers from San Francisco would begin their journey by riding a ferry to Oakland where they boarded trains, this was true for passages to Southern California, the Central Valley, and the San Ramon Branch Line.

Beginning in 1878, the primary route in and out of the Bay Area was from Port Costa to Benicia, over the water by ferry. But with trackage through the Delta, from Martinez to Tracy, less critical trains or traffic to the south used this route. Though there were tracks directly from San Francisco/Oakland to San Jose then south to Los Angeles it was often more economical to send the trains to Los Angeles, via Martinez and the Delta. Much of the rail traffic out of San Francisco was carried across the water by ferry to either Oakland or Richmond. Passengers from San Francisco would begin their journey by riding a ferry to Oakland where they boarded trains, this was true for passages to Southern California, the Central Valley, and the San Ramon Branch Line.

The egress to the Central Valley was relatively flat and trains could travel at high speeds. In the early 1900s, a common locomotive was the 4-4-2, which was a logical  evolution from the 4-4-0. Moving the driver wheels forward provided better traction and balance, while adding another axle to the rear allowed for a large firebox, in front of the cab, to add high-speed power. A larger box means more heat to make more steam for high speed operation. The larger firebox and tall wheels allowed these 4-4-2 locomotives the capability of 100 miles per hour on straight flat track. By the 1920s, the 4-4-2 engines were being replaced in mainline service by the 4-6-2 engines with similar speed but more tractive effort – useful for longer trains with increasingly heavy cars. Many railroads adopted the 4-6-4 Hudson engines in the 1930s, but Southern Pacific did not. Despite this some 4-4-2 locomotives remained in high-speed service until the end of steam.

evolution from the 4-4-0. Moving the driver wheels forward provided better traction and balance, while adding another axle to the rear allowed for a large firebox, in front of the cab, to add high-speed power. A larger box means more heat to make more steam for high speed operation. The larger firebox and tall wheels allowed these 4-4-2 locomotives the capability of 100 miles per hour on straight flat track. By the 1920s, the 4-4-2 engines were being replaced in mainline service by the 4-6-2 engines with similar speed but more tractive effort – useful for longer trains with increasingly heavy cars. Many railroads adopted the 4-6-4 Hudson engines in the 1930s, but Southern Pacific did not. Despite this some 4-4-2 locomotives remained in high-speed service until the end of steam.

Among the named trains on this route were the San Joaquin Flyer and the Owl Limited. The latter, inaugurated in 1898, lasted into the 1960s. These trains operated with several classes of sleeping cars, coaches, chair cars, and a diner. The Owl was popular for business travelers who could board to Oakland in the afternoon and arrive in Los Angeles in the morning.

In 1905 Mountain Copper Company built a copper smelter at Bull’s Head Point, Martinez, close to where the Benicia Bridge is today. At the time this was the largest industrial plant in the area; it became known as MoCoCo, and as a major shipper on the railroad, the track from Martinez to Tracy became known as the Mococo Line. The name is still used today, both for the track and that part of Martinez. The plant is still in operation as ECO Services, producing and recycling acids used by the petroleum refineries.

The type of passenger cars used on the Mococo Line for long distance travel were longer and heavier than those used on the San Ramon Branch Line; these were in the 80′ range, built on heavy steel frames. These became known as “Heavy Weight” cars. To provide a smoother ride, some had poured concrete floors.

Loading the Ferry

In 1878 ferry service commenced taking trains between Port Costa and Benicia. This allowed a much shorter route from Oakland to Sacramento, with entire trains loaded quickly and efficiently. The long distance locomotives could pull the first section of the train directly onto the ferry, but the remaining cars were typically loaded by powerful but nimble “switcher engines” like the 0-6-0. The front and rear wheel sets were eliminated to provide a shorter body, with all wheels providing power and traction. Stability and high speed steam were not needed. For heavier cars they also have 0-8-0 switchers.

The photo above shows a 0-6-0 loading cars onto the ferry Solano in the early 1900s. The 425′ long vessel could hold over 20 passenger cars and a locomotive, or about twice as many 40′ freight cars. There were four parallel tracks running the length of the vessel. Switcher engines pushed and pulled cars around the yards at Benicia and Port Costa along with moving them on and off the ferry.

In the 1950s Southern Pacific was phasing out steam locomotives and relying more on diesels. As early as the 1930s, diesels were becoming the better choice for switcher engines. These didn’t need to drag a cumbersome tender to provide water and oil for the steam engine. Tenders carried mostly water since the locomotives used about 7 times as much water as oil. Some locomotives, called “tank engines” carried their fuel and water onboard, but their ranges were limited. The tank engine is now famous for the cartoon character Thomas the Tank Engine, but it was a real concept common around harbors and industrial plants.

In the 1950s Southern Pacific was phasing out steam locomotives and relying more on diesels. As early as the 1930s, diesels were becoming the better choice for switcher engines. These didn’t need to drag a cumbersome tender to provide water and oil for the steam engine. Tenders carried mostly water since the locomotives used about 7 times as much water as oil. Some locomotives, called “tank engines” carried their fuel and water onboard, but their ranges were limited. The tank engine is now famous for the cartoon character Thomas the Tank Engine, but it was a real concept common around harbors and industrial plants.

The diesels could carry all the fuel they needed in side-tanks, and needed little water except in their cooling systems. These would have become more prevalent sooner had it not been for oil and material shortages in WWII. This postponed the demise of the steam locomotive for about a decade. As the 0-6-0 switchers became obsolete, many were given to cities and parks as historical artifacts. In 1957 Southern Pacific donated #1258 to the City of Martinez, for use in Rankin Park, above where the pool is today. It is seen here while it was still in operation. Despite being a local oriented engine, there are photos of it in Oakland (above) and up and down the Central Valley as far south as Bakersfield. She is now on display at a new location in the Martinez Waterfront Park.

Even though a second ferry had been added in 1914, by 1928 these had reached capacity. At their height each ferry could cycle from Port Costa to Benicia and back in about an hour carrying a train in each direction. There were two shifts of 16 men each providing round the clock service. In 1930, the railroad built a bridge from Benicia to Martinez, making the ferries immediately redundant and obsolete. The 1930 bridge is still in service today after nearly a century of continuous operations.

The San Joaquin Daylight

The 1930s were the high watermark of steam trains in America. Technology was allowing very large and fast locomotives, and with the power to pull heavy trains. The 4-4-2 of 1900 (above) was capable of high speeds on flat-track with a small train. But with long heavy trains more power was needed. Typically a locomotive was designed to focus on speed for passenger service, or power and traction for heavy freight trains. For the most part speed and tractive-effort had been mutually exclusive. To get speed passenger engines had large diameter driver wheels, and typically no more than three per side would fit. For enhanced traction and easier starting with a heavy load, freight engines had evolved to having four driver wheels per side, but these were of smaller diameter. Two very popular engines of the 1920s and 1930s were the very fast 4-6-4 Hudsons, and the powerful but slow 2-8-2 Mikados. In the late 1930s, Southern Pacific took the best of both in the very large 4-8-4 GS (General Service) locomotives. These were capable of 120 miles per hour in passenger service and they could also pull heavy freight trains. They had larger locomotives like the 2-8-8-4 monster, but while it was mighty, it was very slow. In terms of fast passenger engines, the 4-8-4 GS was top of the line, and nothing rivaled it until large diesels evolved.

The 1930s were the high watermark of steam trains in America. Technology was allowing very large and fast locomotives, and with the power to pull heavy trains. The 4-4-2 of 1900 (above) was capable of high speeds on flat-track with a small train. But with long heavy trains more power was needed. Typically a locomotive was designed to focus on speed for passenger service, or power and traction for heavy freight trains. For the most part speed and tractive-effort had been mutually exclusive. To get speed passenger engines had large diameter driver wheels, and typically no more than three per side would fit. For enhanced traction and easier starting with a heavy load, freight engines had evolved to having four driver wheels per side, but these were of smaller diameter. Two very popular engines of the 1920s and 1930s were the very fast 4-6-4 Hudsons, and the powerful but slow 2-8-2 Mikados. In the late 1930s, Southern Pacific took the best of both in the very large 4-8-4 GS (General Service) locomotives. These were capable of 120 miles per hour in passenger service and they could also pull heavy freight trains. They had larger locomotives like the 2-8-8-4 monster, but while it was mighty, it was very slow. In terms of fast passenger engines, the 4-8-4 GS was top of the line, and nothing rivaled it until large diesels evolved.

Along with engine technology passenger cars were revolutionized in the 1930s. Older 80′ cars were built on very heavy steel frames to achieve rigidity. But the concept of unibody became prevalent, where the entire train car is a rigid shell of lighter weight metals. A typical Pullman car of the 1920s weighed about 90 tons. Budd Company was innovative in the unibody concept for both train cars and diesel engines. Pullman followed them into production of the unibody concept cutting the weight by about a third, down to the 60 ton range.

unibody became prevalent, where the entire train car is a rigid shell of lighter weight metals. A typical Pullman car of the 1920s weighed about 90 tons. Budd Company was innovative in the unibody concept for both train cars and diesel engines. Pullman followed them into production of the unibody concept cutting the weight by about a third, down to the 60 ton range.

In 1937 Southern Pacific launched the Daylight series of trains, following the national trend of colorful sleek looking locomotives with fancy paint jobs. In the east many railroads were encasing their steam engines in streamlined sheet metal, emulating the looks of early diesels. In many cases the machinery was completely covered. The Daylight engines had a half-measure. They had a flat decorative panel running from front to back covering the side of the engine, and this gave an opportunity for a bright paint job — emulating the streamlined effect rather well.

The San Joaquin Daylight was introduced in 1941, just before the US entered WWII. It ran through Martinez going from Oakland to the Mococo Line and then through Tracy into the Central Valley on its way to Los Angeles.

Dining Car

For most of the history of train travel in the US, onboard dining has been part of the experience. On major trains like the Daylight series, meals were prepared onboard and served by the staff as though it was a rolling restaurant. The dining cars were typically in the middle of the train so that all classes of passengers could get direct access. The kitchens were typically all stainless steel from floor to ceiling, and the dining areas were a series of 4-top tables with chairs. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner menus offered a wide selection of food and beverages.

For most of the history of train travel in the US, onboard dining has been part of the experience. On major trains like the Daylight series, meals were prepared onboard and served by the staff as though it was a rolling restaurant. The dining cars were typically in the middle of the train so that all classes of passengers could get direct access. The kitchens were typically all stainless steel from floor to ceiling, and the dining areas were a series of 4-top tables with chairs. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner menus offered a wide selection of food and beverages.

Our display features Southern Pacific dishware in the Prairie Mountain Wildflower pattern. This pattern was first featured in 1931 and was a popular pattern for the rest of dining car service into the early 1960s. The upright plate is a very early example with the flowers out to the rim. The other pieces are from a later series known as Econo-Rim, which were a bit smaller supposedly to accommodate tighter spaces in lightweight dining cars.

The Shasta Daylight

After the success of the Daylight concept, begun in 1937, Southern Pacific decided to transform the Shasta Limited into the Daylight pattern. This train had been in operation since 1895 and was very popular due to the amazing scenery. The Shasta Daylight would be an all lightweight train led by diesel power. It was a 15 1/2 trip from Oakland to Portland, cutting the time nearly in half from the old steam led heavyweight trains.

After the success of the Daylight concept, begun in 1937, Southern Pacific decided to transform the Shasta Limited into the Daylight pattern. This train had been in operation since 1895 and was very popular due to the amazing scenery. The Shasta Daylight would be an all lightweight train led by diesel power. It was a 15 1/2 trip from Oakland to Portland, cutting the time nearly in half from the old steam led heavyweight trains.

Service began in 1947 being pulled by two EMD F-units, but soon this was switched to the new Alco PA which had two V-16 diesel engines in each locomotive. These trains also had dome cars allowing better views for the passenger.

The route was from Oakland to Martinez, then over the bridge to Sacramento before heading north past Mt Shasta.